Always show, don’t tell! (Unless you are Alan Ball, remember? 🙂 ) Today, I’ll show you a perfect example of that “always show, don’t tell” rule. The movie was written by John Michael Hayes and directed by Alfred Hitchcock – the ultimate master of cinematic storytelling.

Quite early, we are introduced to the main character played by James Stewart. What is interesting though, is that the introduction happens through one single camera movement. Nice!

On imsdb.com, there is a script to Rear Window. I don’t know whether it is the original screenplay or just a transcript. Nevertheless, the opening scene is described there very nicely. So the following words are not mine, but the words found in Rear Window script.

The camera starts in the backyard, then pulls back swiftly and retreats through the open window back into Jefferies’ apartment. We now see more of the sleeping man. The camera goes in far enough to show a head and shoulders of him. He is sitting in a wheelchair.

The camera moves along his left leg. It is encased in a plaster from his waistline to the base of his toes. Along the white cast someone has written “Here lie the broken bones of L. B. Jefferies.”

The camera moves to a nearby table on which rests a shattered and twisted Speed Graphic Camera, the kind used by fast-action news photographers.

On the same table, the camera moves to an eight by ten glossy photo print. It shows a dirt track auto racing speedway, taken from a point dangerously near the center of the track. A racing car is skidding toward the camera, out of control, spewing a cloud of dust behind it. A rear wheel has come off the car, and the wheel is bounding at top speed directly into the camera lens.

The camera moves up to a framed photograph on the wall. It is a fourteen by ten print, an essay in violence, having caught on film the exploding semi-second when a heavy artillery shell arches into a front-line Korean battle outpost. Men and equipment erupt into the air suspended in a solution of blasted rock, dust and screeching shrapnel. That the photographer was not a casualty is evident, but surprising when the short distance between the camera and the explosion is estimated.

The camera moves to another framed picture, this one a beautiful and awesome shot of an atomic explosion at Frenchman’s Flat, Nevada. It is the cul-de-sac of violence. The picture taken at a distant observation point, shows some spectators in the foreground watching the explosion through binoculars.

The camera moves on to a shelf containing a number of cameras, photographic film, etc.

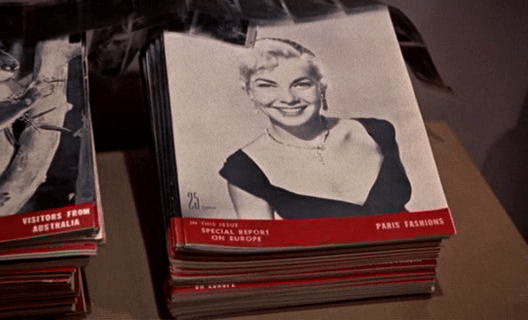

It then pan across a large viewer on which is resting a negative of a woman’s head.

From this, the camera moves on to a magazine cover, and although we do not see the name of the magazine, we can see the head on the cover is the positive of the negative we have just passed.

From this, the camera moves on to a magazine cover, and although we do not see the name of the magazine, we can see the head on the cover is the positive of the negative we have just passed.

So through that one single camera movement, we know:

- where we are

- who is the main character

- his name

- his profession

- all about his work

- what caused the accident

Now, that is a very cinematic introduction of the main character through one single camera movement, not a single frame was wasted. And here is what Alfred Hitchcock said himself about this opening scene:

That’s simply using cinematic means to tell a story. It’s a great deal more interesting than if we had someone asking Stewart: “How did you happen to break your leg?” And Stewart answering: “As taking a picture of a motorcar race, a wheel fell off from one of the speeding cars and smashed into me.” That would be the average scene. To me, one of the cardinal sins for a script-writer, when he runs into some difficulty, is to say: “We can cover that by a line of dialogue.” Dialogue should simply be a sound among other sounds, just something that comes out of the mouths of people whose eyes tell the story in visual terms.

The paragraph above comes from a book called simply Hitchcock. It’s a collection of interviews between Alfred Hitchcock and François Truffaut and I have to tell you, this is such a beautiful book! ♥

It’s a journey into the world and history of cinema, Hitchcock’s personal life and first of all, a unique look at his films. Can’t wait to read that book again, and again, and then again!